Most people do not question the institution of private property. Changes that are needed in land use- both for ecological reasons and for a better agricultural system- are all meant to happen within the current system of land ownership. However, some question whether this will be possible. Olivia Oldham, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh, argues in an interview with the People’s Land Policy (as well as at the recent Oxford Real Farming Conference), that too much private property ownership is in fact an obstacle to any urgently needed reforms in land use.

Olivia Oldham writes:

An important way of thinking about carbon credits and natural capital is as things that the law makes. The law is foundational to transforming the world into capital, marking out boundaries between what is a public or common good, and what is privately owned property, able to generate wealth for its owners. Natural capital and carbon offsets are just new kinds of legally constituted private property, central to the “neoliberalisation of nature” – where parts of ‘nature’ or natural values are separated from their context and transformed into abstract ideas. Complex soil webs of life become a unit of sequestered carbon, a unique wetland ecosystem becomes interchangeable with any other wetland, both able to be sold on the market to the highest bidder.

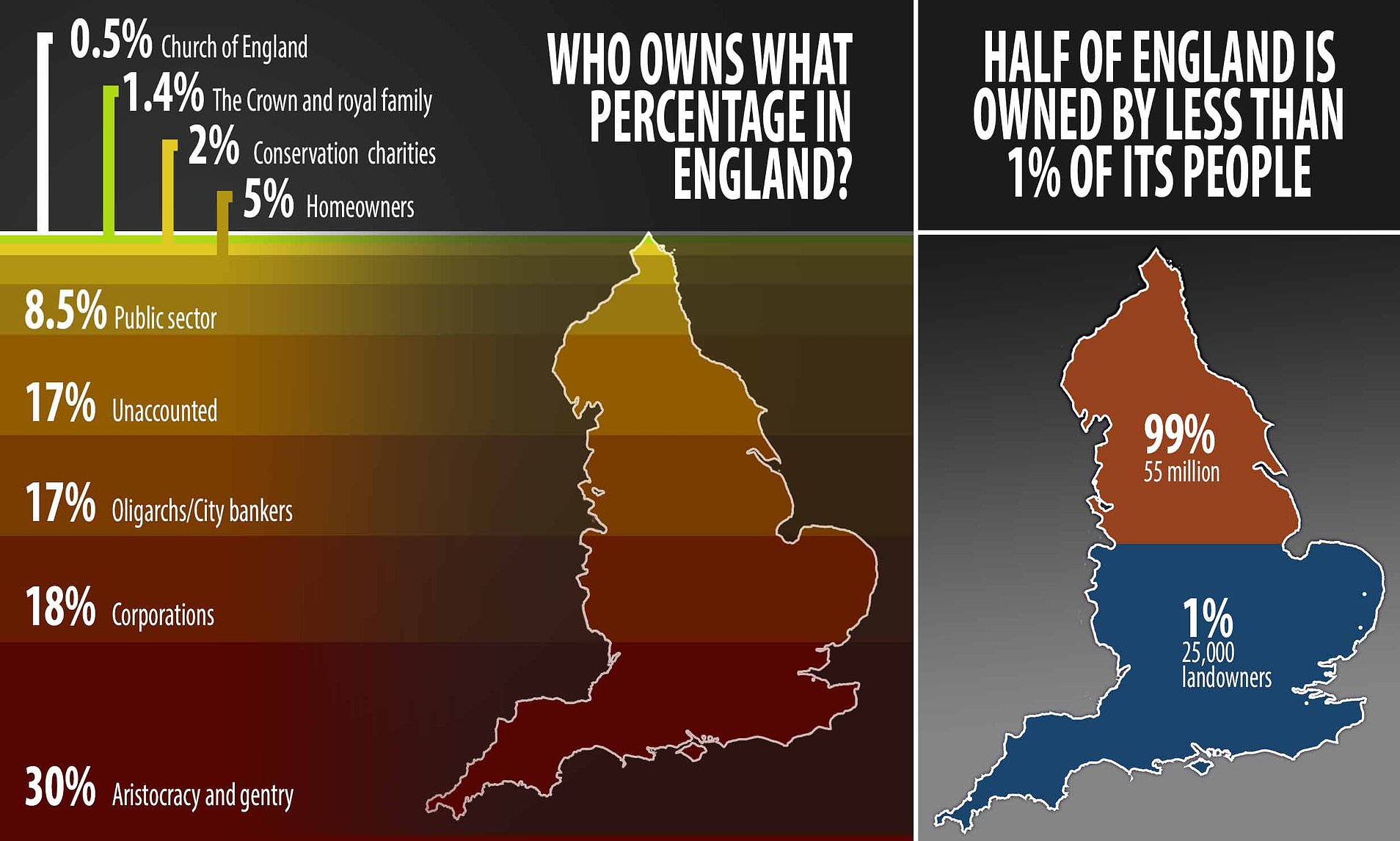

But while it’s easy to assume that property and the law that governs it are somehow fixed, even natural, it’s important to realise that property relations are the consequences of deliberate choices about how society–and ecology–should look. Property is fundamentally a social relation. And while advocates of private property argue that it advances important values like freedom, justice, and democracy, this isn’t necessarily accurate. Freedom for who? Justice for who? Who gets a vote in a democracy of property owners?

In reality, dispossession is nine tenths of the law. If you go back far enough, private property is almost always based on someone taking something from somebody (or, usually, a group of somebodies) else. So when we think about natural capital and carbon offsets, we can think of them as a form of enclosure of public or common goods, a process that is put into action by the law of property. The way the law works to create these private formations of property tends to reinforce racial, gendered and other forms of social hierarchy.

But property is socially constructed, and it can be made differently. There are other ways of managing the natural wealth of our world–ideas like the commons, reframing rights as responsibilities, or even understanding the living world as kin. These might be more promising mechanisms for dealing with issues of environmental degradation than the options usually put on the table today.